Parkdale, Sept. 1

First day: Parkdale Amphitheatre (also known by the residents as “the Parkdale Parquette”) located just West of the Queen and Dufferin underpass, 11:00 AM-1:00 PM

The TiP lab received a warm welcome by residents and passers-by, thanks to a group of supporters coming from the community, and to our location just meters from the Queen streetcar stop. It is not surprising that among the first items we received was an old transfer and a cigarette butt, the latter a dense symbol that not only evokes waiting and impatience, but also addiction and transience.

During our short stay, we had a direct experience of the hectic flows that populate the city in general and Queen Street in particular. People, infrastructures, natural and urban environments form an uneven ecology: mothers tend to their children while waiting for the streetcar to and from home; individuals walking their dogs; workers on their way to work; curious passers-by; members of PARC, where we had done some community outreach in the previous weeks, came to visit us and donated words, songs, stories, artwork…

Among the many casual encounters, we came across some unexpected connections. A woman stopped by our lab to check out the photos of past Parkdale, which we had retrieved from the Toronto Archives and we had transferred on transparent plates (some ghosts from the past). She recognized the pictures…her father had collected and donated them to the archives.

A man waiting for the streetcar kept coming back (and missing the streetcar several times) to tell us one more story and to engage with other participants.

A woman asked us what we were doing and was overjoyed to hear that she could write her Parkdale story. She sat on her knees for a long time, unbothered by the scorching midday sun and wrote. A little girl donated us flowers and drew a silhouette of her little hand.

Stories of gentrification loomed large in people’s comments. Attitudes were mixed, and different perspectives overlapped and rubbed against one another, revealing hidden tensions among the comings and goings of a busy work day on the street.

A few artists, residents of Parkdale for decades, lamented how increasingly prohibitive it has become to live in Parkdale. They were all extremely aware of the dire irony of a neighbourhood that has now become inimical to the very people who first contributed to its revalorization.

On the other side of the divide, a young well dressed man stopped by to check us out. It turned out he had just bought a condo across the street and was very happy with it. I asked him if he had chosen to live in Parkdale for a reason, and what I got was a story of reluctant return to a neighbourhood that had been his first safe haven from war. A refugee from South Sudan, he had arrived in Parkdale in the early 2000s. He told me he didn’t mind it at the beginning. He had lived in Cairo for a bit before making his way to Canada, and found Toronto a lot safer than Egypt. But his was not a love story with Parkdale. He had ended up there because it was the cheapest part of the downtown core to live in for someone arriving with nothing. He moved out as soon as he could, citing the neighbourhood’s bad reputation for drugs and violence as his reason to leave. And yet, he has come back, and now seems to be happy with the new veneer of respectability the neighbourhood has acquired — happy, yet possibly oblivious to the kinds of social costs attached to its gentrification and the new visible presence of affluence therein.

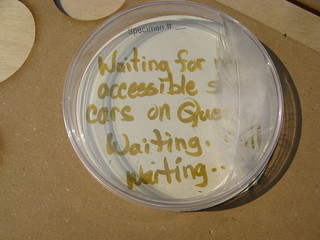

Stories of mobility and accessibility were passionately shared with us by some members of PARC — a community centre whose activist presence in the neighbourhood for the past 30 years has provided some degree of resistance against the aggressive effects of real estate make-over, enabling people to live with dignity despite systemic forces of marginalization preying upon them (poverty, mental health, addiction), through initiatives such as the Parkdale’s People Economy, the Coop Cred Program and other programs meant to provide supportive social, psychological, economic and creative networks for people to rebuild their lives. Our friend, S., in particular, shared her observations around mobility and the new problems now emerging from the increasing presence on the street of mobility devices, the neighbourhood’s increased density of population, and new tensions emerging from having to negotiate narrow sidewalks with people who only want to get from one point to another as fast as possible. She called for more literacy program about sharing pedestrian space in both respectful and dignified ways.

The issue of accessibility — and possibly of the ableist assumptions governing our approach to the lab — was brought home to me by two awkward encounters. One person stopped by, very curious to see what the lab contents were. I immediately approached him and started talking enthusiastically, asking if he wanted to contribute a story. His reaction was polite but firm. He stepped back, gestured with his hands to his ears and then made a no sign. He could not hear me. He left.

Later, during a lull in the steady stream of people approaching us, I decided to walk over to the streetcar stop and approach a woman sitting on the outer ledge of the amphitheatre with a transparency of old Parkdale in my hand. I only noticed the walking cane folded on top of her bag after I invited her to check out what that particular corner of Parkdale looked like a 100 years ago. Her answers were polite, and she mentioned having lived in the neighbourhood for the past 15 years, and liking it. The transparency was not talked about in the exchange. I was grateful for her graciousness, but was made poignantly aware of my implicit ableist assumptions in my approach.

Other stumbling blocks of mistranslation and misunderstanding also appeared that day: such as the Asian man who first approached us great curiosity and started chatting, but then got quite incensed when I asked him — with clipboard in hand — “why do you come here?” (meaning “what brings you to this neighbourhood, what do you like about it”), after I learned he no longer lived in Parkdale. He got upset at my question, and told me it was the wrong question to ask. He said he had come to Canada long ago, and in short, I had no business asking him that kind of question. My attempt to explain the misunderstanding only seemed to make things worse. I was obviously perceived as belonging to some kind of government agency doing surveys (and possibly surveillance), and the exchange stopped there.

Roberta reminded me that it is election time, and people’s wariness around meeting people with clipboards asking personal stories of them is more than justified. Still, that incident and others I would have over the next few days, made me aware of the limits of perception and of how our own gendered, white, apron-clad and accented bodies would be perceived on the street. Definitely not everyone was comfortable approaching us, and the range of stories we have collected so far were (and will continue to be) shaped by what our public presence on the street is perceived to signify.

Interestingly enough, the next day, in Trinity Bellwoods Park, the most common source of misunderstanding was in no way related to migration and surveillance. It was related to money. The most common answer we would get to our question: “What you like to contribute your story to our TiP lab?” was not “Sorry, I have to run, no time to stop”. No, it was “Sorry, I don’t have change on my right now…”

Now, what does that say about a neighbourhood’s gentrification? But that’s a story for tomorrow’s blog on Trinity Bellwoods…